Why could I not remember this place?

The morning sun lit the mirror of the lake and set ablaze the snow-capped peaks of the surrounding mountains. Miles away in the Massif des Écrins I heard the crack and rumble of ice shearing from rock and the occasional thunder of cornices collapsing in the warmth.

We’d spent so many of our holidays here, our little family, in the auberge beside Lac-Saint-Patrice. It’s where my parents first met on a hiking holiday, he from his home in North London, she from her native Lyon. They’d both fallen in love with the alpine landscape and the more intimate scenery of each other’s smiles. They’d married, raised children and hoped to imbue in us a similar love for the outdoors by way of regular family holidays to this place—this place I could not remember.

At least, that’s what my father told me.

“We were happy once,” was another thing he told me. He said this often, as if it was a revelation, some lost history, scratched out and forgotten. He wanted to assure me I was born out of love, not sadness. He repeated the phrase over and over, perhaps because he thought I could never accept the fact as truth, not in the aftermath. But I never doubted him. I just couldn’t remember a time before it all fell apart, before Lorens died. Life, for me, began after.

I explained this to him once, and I remembered his reply. “The mind forgets what the heart regrets.” Yet what I could have regretted so deeply was beyond me.

This place, and that past, had not entered my thoughts for many decades. Until last night.

I was working late at the university, resisting boredom and the loneliness of my cramped apartment by researching the topic that has obsessed me for a lifetime: nature versus nurture. It’s one of the last big questions; one with no empirical answer: are we born innocent, a clean slate, a tabula rasa? If so, then it is the world that shapes the evil in our hearts. Or do we enter the world corrupt, and so shape the world in our own image?

It’s a question that may never be answered.

Am I good? Am I evil? Is this why the subject pulls at me so? Am I searching for my own absolution? When I look into my soul I see no answers. I sense a form of goodness, innate and protean, but there’s a shadow here too. Something old and formless.

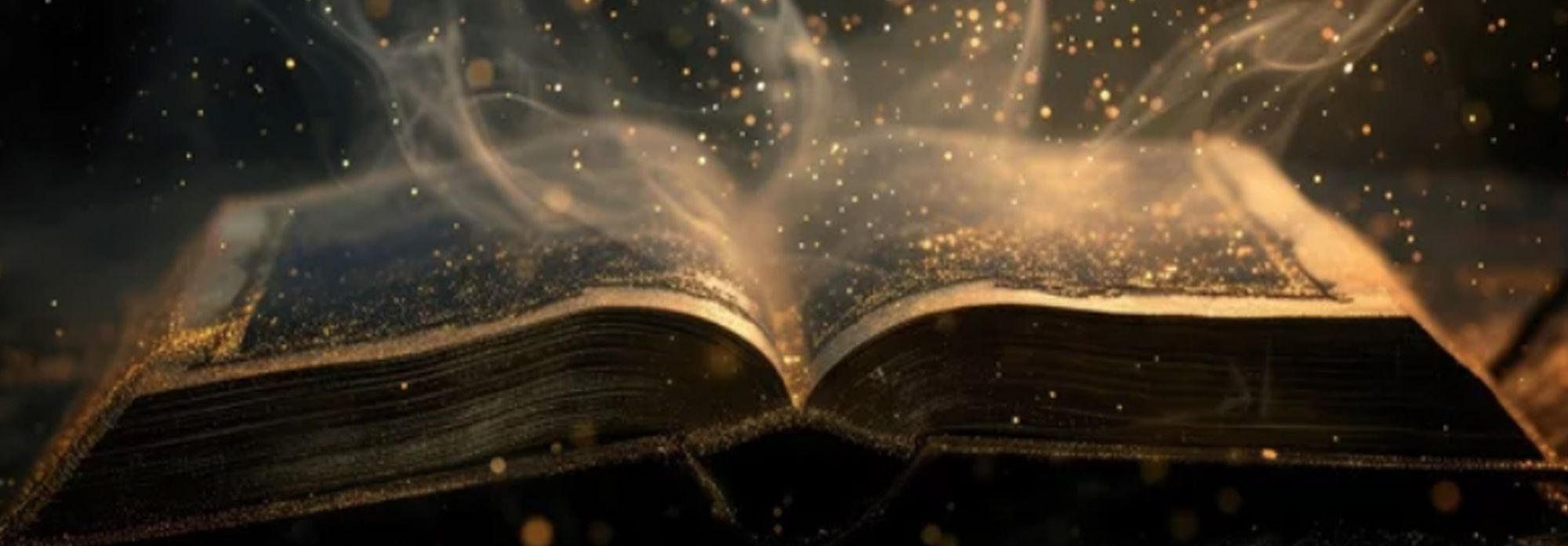

From my bookshelf I had pulled a dog-eared volume of essays by Rousseau. I hadn’t read it since my undergraduate years. As I opened the book, a photograph fluttered from its pages to the floor. Stooping with a groan, I snatched it up. It looked unfamiliar at first, yet as I recognized it, something pulled at my insides, a stitch of nostalgia that tied me to a time long past, to something that was, and is no longer. I had once used this old black-and-white print as a bookmark.

The photograph must have been taken by my father because he was the only one missing from the composition. It struck me how beautiful my mother was as a young woman. I had forgotten the thick, raven-black hair, the graceful brushstroke of her dark eyebrows and lashes that framed the pools of languor that were her eyes. In the photo I snuggled next to her, my eyes lifted to hers in adoration. Hers were turned away from me and rested on the infant sitting in her lap. Lorens. He was the only one who faced the camera. Eyes squeezed shut in mirth, he was captured mid-chuckle. Chubby, cherubic and lovable, he was joy made flesh. Jove as a baby.

I sat at my desk, resting heavily in my chair, the photograph shaking in my hand. I thought without thinking, my mind drifting through clouds of patchy memory in search of the past. An hour must have slipped away before the impulse seized me. It was more of a whim than a conscious decision, a plan without forethought, a sudden need. I locked my office and drove to my apartment. There, I packed a few things: a raincoat, some warm clothes, my old leather hiking boots and a knapsack. It was late when I left Villeurbanne, but the roads were quiet. I drove southeast, turning off the well-lit motorway at Bourgoin-Jallieu. Within a few hours I was driving along unlit country roads. Tomorrow I would call the university to advise them of my absence. It wouldn’t be a problem. I no longer have students. I give the occasional lecture, nothing more. This suits me. I find students, like most people, invasive and needy. They steal my time and contribute little in return. I am better alone. It gives me space to think, to indulge myself in research of my own choosing. My only qualification for this continuing arrangement was a paper I’d written some forty years before. It questioned whether good and evil exist in the natural world or remain human constructs, ways to feed our righteousness and our guilt. The paper excited debate and is still quoted and referenced today. The university enjoys the renown this brings and so they keep me on, happy to have me haunt the hallways filled with youthful faces, a white-haired specter with armloads of books. Perhaps they think I add a sense of antiquity to the place—of gravitas—as much as the stern-faced busts of Voltaire and Descartes. Like them, I am a man who once was. I am become a name. A footnote in a thesis. My absence will not be a problem. Such is the privilege of age and reputation.

Here beneath the mountains, I planned to visit the dark ages of my childhood, to peer into the blind spots of my past. I was hoping that the permanence of the geography might trigger a recollection in my inconstant mind. I longed to remember what happened before death visited our family, before my mother fell inwards upon herself, shutting me and my father out.

“She’s just gutted, son,” was the only explanation my father could offer in his North London way. In my immaturity, I took him at his word and believed that my mother had been secretly sliced open and her organs removed. As I came to understand the expression as imagery, the more appropriate it seemed. My mother had indeed been gutted: she had no stomach left for the world, no lungs to give her breath for speech or laughter, no heart to help her feel. Gutted was right.

My father tried to insulate me from the worst of the damage. I was sent to a boy’s boarding school in Chatres and, in many ways, I never returned. My mother never called or wrote to me. I’d hoped that after Lorens, her heart might let me in. Perhaps she saw the shadow in me. Perhaps she was made to love only one of us.

She moved back to Lyon, to live with her sister or a cousin, I think. My father visited her but she was beyond consolation. He tried as hard as he could, offering love without reciprocation, support without thanks—a vessel slowly emptying itself. In each other’s eyes their grief would always be mirrored; their loss, their sense of guilt, shared. Together they would never heal. So my father drifted back to London, to a life before marriage—a life that didn’t hurt. By the time I left school our little family had crumbled and fallen apart. Like a cornice in the sun.

The first flurries of snow melted on my windscreen. From Bourg d’Oisans the road began its slow climb into the Alps, along the pass of the Col du Lautaret. In the darkness I saw nothing of the forests or the grandeur of the mountains. I phoned the auberge from the road and, mercifully, the concierge was still awake. A room was made up and a cold supper prepared. As I pulled into the car park, my headlights swung across the emptiness above Lac-Saint-Patrice. My sleep was troubled by old dreams. I woke at the sound of my mother’s whisper in my ear, her hand upon my shoulder. Rousing, I knew the dream was a falsehood, its knowledge painful. My mother had never woken me this way. Soft words and gentle hands were reserved for Lorens.

It was early as I laced my hiking boots. The auberge was still quiet. At the breakfast buffet in the empty dining room, I wrapped some fruit and boiled eggs in a serviette, stowed them in my knapsack, then crept outside. A chill dawn washed the sky with pink and lavender. Soon the sun would crest the mountains. For now, the trees and lake brooded in darkness. Silence hung in the vastness of the landscape as if frozen.

There was light enough for me to find my way down to the gravel path that circumnavigated the lake. I began to walk, with mounting vigor and purpose as the light improved. The air was sharp in my nostrils. Some distance from the auberge, the path narrowed to a rocky track. It rose and fell behind stands of tall firs and birches that hid the lake. I slowed, glancing through the trunks to catch the occasional gleam of flat water. If I had walked this track before, I couldn’t recall.

By the time the sun had painted the landscape in all the glory of its true color, I was at the halfway point around the lake. Here the hourglass shape of the lake narrowed, and a rocky outcrop looked over the water in the direction of the auberge. The old building itself was screened from view by a rise of trees. The distance from shore to shore was no more than a hundred meters and I had a sweeping view of the lake in all directions. I drew in a lungful of crisp air and became lost in the scene. It was a masterwork. And still, I could not remember it.

I leaned back against a rock, pulled a boiled egg from my knapsack and began peeling it with a thumbnail. In my periphery flashed an intrusion of color, something brash and inappropriate that trespassed against the blues and greens of water, trees and sky.

Looking up, on the opposite shore of the lake, I saw a little boy, no more than a toddler. He wore an anorak of vivid yellow and matching gumboots. In his hands was a long, windblown branch which he held out over the water like a fishing rod. He slapped the water with the tip of the branch in some private game. In the still air, snippets of a rhyme or song drifted toward me. The little fellow seemed delighted at the splashing and at the ripples he was now causing to widen across the lake.

I returned to the peeling of my egg. Piece by piece, the shell came away as, piece by piece, a dark thought formed.

A mother would have realized the danger in an instant. But too selfish to ever have children, I was slow to understand, too slow to read the situation. I looked again. The child stood on a shallow bank of grass, close to the water’s edge. He was perhaps only four, maybe five years old, and unlikely to be a swimmer. Concerned now, I placed the egg back in the serviette and dropped it into my knapsack. I searched the distance, trying to see the auberge through the trees. An adult or parent must be nearby, perhaps watching from the terrace. I craned for a better view but couldn’t make out the terrace or the building itself. Even if someone was observing the boy from an upstairs window, they’d be too far away to prevent catastrophe. I couldn’t even see the roof, which only meant the auberge was hidden behind the trees, behind the hill. This little fellow was all alone.

I squinted against the glare of sun on water, looking for someone nearby. I searched the shade beneath the foliage of the trees, between the trunks. Just a short distance from the boy stood a tall willow that veiled the lake shore. Its branches cascaded down to the same water from which its roots no doubt drank. Between the partings of rope-like limbs, I glimpsed shadows. One such shadow looked different. It was tall, slender, and motionless in the gloom under the tree. I focused my attention on it. My eyes watered. I blinked.

The shadow moved.

I glanced at the toddler by the lake. He was happy, still immersed in his game.

Looking back to the shadow, I saw it move again. It was person shaped. Someone was standing in the shade of the tree, watching.

Relief washed over me. It must be a parent, disinclined to take part in the childish game, but performing their duty of care, nonetheless. Of course, they’d stand in the shade of a tree to stand guard. I would too. I shook my head at my over-reaction and bent to collect my breakfast just as the shadow broke cover.

I stood upright in time to see the figure step into the sunlight. It was another boy. He looked to be a good four or five years older than the first. No parent, no adult at all, and not quite a teenager. He stood motionless, as before, watching. Something about this boy prickled my skin. Although the smaller boy’s happiness was clear to see, the older boy’s mood was unreadable. For several minutes he stood with eyes fixed upon the smaller boy. Perhaps it was the distance, or my untrustworthy eyesight that caused me not to see any expression in the newcomer’s face.

He walked over to the younger boy and stood beside him at the edge of the lake. He gazed with ambivalence at the tip of the branch splashing the water. The younger child must have heard him by now, must have been aware of his presence, but his game continued. It could only mean that they knew each other. This should have brought me comfort, yet a fear floated up from the depths, unfounded and irrational. I was scared for the little one and I didn’t know why.

The older boy placed a hand on the toddler’s shoulder. I was right, they knew each other. My only hope was that the older of the two could swim, and that he was there to keep the younger boy safe. I took a bite from the egg I’d peeled and continued watching.

The older boy removed his hand from the other’s shoulder and walked a short distance along the grassy bank. Then he stopped and pointed at something in the water, calling out to the smaller boy. A fish perhaps?

The younger boy’s sounds of glee traveled to my ears across calm water in still air. He dropped the tree branch and stumbled towards the older boy, clumsy in his yellow gumboots. He stood beside the other, leaning forward to peer at whatever was in the water.

The two bent low over the lake, the elder pointing, the younger following the direction of the other’s finger.

It happened in an instant.

I saw no push from behind. There was no violence, no display of force. All I saw was the older boy’s hand, not the one he’d been pointing with, but the other one, the one hidden behind the smaller boy’s back. It was now raised palm outward as the smaller boy tumbled into the water with a cry.

Although I hadn’t seen it, I knew what had happened. All it took was a nudge.

The yellow anorak buoyed the little mite up. Through mouthfuls of water he squealed, hands raised in appeal. The older boy looked on, impassive. The water couldn’t have been deep because the little boy seemed to gain a foothold, his shoulders rising above the surface of the water. He blubbed, stricken with fear and cold. The older boy looked about now, up and down the shore, and his eyes seemed to rest on the discarded branch. In three quick steps he had it in his hand and held it out to the younger boy. I had imagined the worst. Foolish old man. It was all an accident, and now the older boy would drag the younger one to safety.

The little boy reached for the tip of the branch, his footing unstable. At the last moment, before his fingers closed around it, the older boy whipped the branch away. I felt my mouth fall open; my heart shuddered to a stop. Again, the older boy held out the branch and again he pulled it away at the last second. What was he thinking? Was this a game to him? His face still displayed no emotion and for a moment I considered he might be unbalanced, without conscience enough to understand what he was doing. The child in the water was screaming now, wild with fear. My short-lived relief sank into the depths, replaced by a searing anger. I screamed, too, but a cold, mid-morning breeze left the peaks and blew across the lake toward me. It bent the tops of the fir-trees in my direction and stirred the surface of the water. The harrowing cries from the opposite shore of the lake still reached my ears but my entreaties were blown back in my face.

The little toddler again found a foothold and was struggling from the water. The older boy lowered the branch in his direction and the toddler grasped the leafy tip with shaking hands.

But the older boy didn’t pull him in.

Instead, he pushed.

I shouted into the wind as the poor little chap fought back. The older boy snatched the branch away from the toddler’s hands and thrust it at his throat and face. He pushed hard, leaning out, forcing the younger child into deeper water.

I looked at the path on either side of me. Which way was quicker? I attempted a hasty calculation of the time it would take to reach the other side of the lake and put an end to this brutality. I’d never make it. Could I run? I hadn’t run in years. If I could bear the pain of grinding hips and arthritic knees I might reach them sooner, but not by much. A roar of frustration left me. The little toddler knew the danger he was in. He was fighting for his life now, thrashing the leaves and stems away from his face, pushing with all his strength against his assailant. He turned, trying several different routes to reach the bank, to avoid the thrusts of the branch, but the other boy moved quickly in front of him, blocking his escape and forcing him back. The wind carried the little boy’s desperate screams across the lake. Better that I stay where I am, in plain sight. I still had a good view up and down the lake. The screams were torture. I clapped my hands over my ears. My best hope was for someone from the auberge to appear, or another walker on the path. I could wave a warning, shout a message. If I could only get the older boy’s attention, he’d know he had a witness. It might shame him into stopping.

I called against the wind through cupped hands. I threw stones, I waved my arms and still the cruelty continued. The little boy was exhausted now. He splashed around in the water, listless and terrified. He sobbed. He cried for his mother. His begging tore at me, but the older boy remained stonily unresponsive. How callous. How heartless. Now, he hooked the end of the branch into the hood of the toddler’s yellow anorak. He held it out straight, preventing the younger child from climbing out, immobilizing him and forcing him to tread water. He held it this way for some time, draining the younger child’s energy while he splashed and floundered. All I could see was the yellow hood and tiny hands that flailed above the water. There came a spluttering and gasping for breath, a last waterlogged plea for mercy. Then the yellow hood sank below the water.

I breathed in shallow gasps. My eyes remained on the older boy. He flashed a look to either side and over his shoulder in the direction of the auberge. He was checking his crime hadn’t been observed. But he didn’t look in my direction. It was then, to my amazement, that he pulled on the branch, lifting the younger child to the surface, dragging him toward the grassy bank. The toddler moved. He was alive yet.

Both hands on the branch, the older boy regarded the child in the water. There was a cough. The smaller boy writhed, still pinned by the branch tip in the hood of his anorak, but the older boy didn’t pull it free. Instead, he lifted the opposite end until it was vertical and moved his hands upwards along the branch. He stiffened and drew himself to his full height. Then he arched his back and drove the branch downward, plunging the little boy under the water by the hood of his anorak.

I screamed another unheard plea into the wind. The older boy leaned upon the branch, using his weight to drive it down and keep his victim submerged. He remained like this for some time. Five minutes? Ten? I watched little fingers and yellow gumboots froth and splash the surface of the water until they stilled.

The older boy relaxed and let the drowned child float to the surface. With a final thrust of the branch, he pushed the body away from the shore. It drifted towards me, slowly sinking, the yellow anorak blending into the blues and greens of the lake. There was bubbling, and the child in the water was gone.

I slumped back against the rock, my anger cooling. I only felt grief, a sorrow as deep and cold as any lake. My grief was for the little boy in the water, but something else besides—something larger, more universal, a wearying, leaden sadness for us all. If children can murder, what hope is there for any of us?

Here, near the closure of my life, I finally had my answer. We do not enter this world as a blank slate, as tabula rasa. Our slate is written upon—filled with every preordained sin, every evil of which we are capable. We are all guilty of that first, most barbarous of crimes. We all carry Cain’s mark. We are all sons of Adam. Our higher purpose is in not giving these evils action. We are here to choose. This is our only redemption.

Against the skin of my face, I felt the wind drop. Looking up, I saw the surface of the lake become a mirror once more. The boy watched the water where the smaller child had been. He seemed lost in thought. Whether it was remorse or gratification I could not tell.

I stood, raising a hand to shield my eyes from the glare of sun on water. With the other, I pointed in accusation.

“I saw you!” I shouted. “I saw what you did!”

My voice reached him, and he looked up, his brows gathering. He lifted a hand to shield his eyes as I did.

Something in the cosmos gave way, like the shattering of floodgates, a river bursting its banks. From far away I heard the deluge roar as the watershed of memory broke open. The mind forgets what the heart regrets. It surged toward me in a mountainous wave, apocalyptic with revelation. All that I had hidden, all that I had dammed up, now came flooding back.

I remembered.

I remembered this place.

I was a boy of nine again. I stood beside Lac-Saint-Patrice on a summer morning. With one hand I shielded my eyes from the sun. In the other I held a windblown branch. I looked across the water and the years, to the opposite shore.

There, his hand shielding his eyes in the same way, was an old man.

An old man looking back.